“Take Pashmina with you,” Mother said, and Raina could tell by the jut of her hip that it would be no use to argue.

It was bad enough that she had to fill the water jars today. She had already done all of her own chores, and the water jars were Adnan’s responsibility. But this morning Father had announced that 12 year old Adnan was old enough to accompany him across the valley to the district marketplace. There they would sell the sweet potatoes that Raina and her mother and sisters raised in the tiny garden plot beside their hut.

Raina longed to go to the marketplace, but she knew better than to ask. Even though she was the oldest, older than Adnan by three years, Father always looked through her when she spoke. It rankled, though she tried not to think about it. Women, Father was fond of saying, were meant to be of serene countenance and peaceful spirit. Mother always looked serene when Father was around. It was only when he left the hut that Raina and the two younger girls felt the sting of her tongue and saw the fiery spirit that lived in her eyes.

That fire was there now, and it was why Raina swallowed the objections that sprang to her lips. Instead, with an inward sigh, she picked up the two water jars and called to Pash to follow her to the river.

The four year old girl toddled along obediently, thrilled to be on an adventure with the big sister that she idolized.

Wide-fronded ferns and the dark green leaves of flowering hibiscus bowed down over the well-worn path. Raina hurried along, ignoring the colorful blooms, anxious to be done with this chore so that she could meet Arjun behind the village stables. She was already late, but she couldn’t exactly tell Mother that. She blushed to think of what Mother would say if she knew about the furtive kisses Raina had shared with the Elder’s son there in the straw-scented darkness.

Before long, the encroaching greenery of the forest gave way to the soft, flat grass that covered the sloping bank of the river. The dark water flowed slow and deep, and an occasional ripple broke the surface where the river carp rose to grasp at the water bugs that skimmed through the late morning mist.

Raina looked around for Pashmina and found her a few steps away, trying to coax a shiny black frog onto a stick.

“Remember not to get too near the edge of the water, Pash,” she reminded the girl. The bank dropped off suddenly past the edge of the water, and more than one small child had been lost to the currents beneath the deceptively calm surface, pulled down by the swirling eddies into the shadows and the mud.

Tucking the jars securely beneath her bronze arms, she stepped out onto a large flat rock that jutted out into the river, careful to spread her weight out for balance. Then, easing the lids off of the jars, she stooped to fill first one and then the other with cold, clear water.

She carried them to the edge of the trees one at a time, then stood and pondered how she might get both jars home without making two trips.

A terrified shriek tore across the mist from the direction of the water.

Raina startled, kicking over one of the jars. “Pashmina!”she cried. Her long legs carried her to the edge of the water, where she scanned the surrounding area, frantic to find her sister. “Pash!”

Another long scream sounded from her left, and Raina swiveled her head to find its source. There she was, crouched at the precipice of the bank, her chubby fingers clutching at her own dress in alarm, her eyes enormous pools of black in her face as she stared toward the water.

Before Raina could take even a step in that direction, an enormous, scaly shape rose like a demon from the deep and snatched the girl from where she stood, cutting off her watery wail with one snap of its cavernous mouth.

Frozen with shock, Raina tried to make sense of what she’d seen. A fish! No, surely not a fish. No fish grew so immense as that, even in this deep part of the river. It was impossible. But that was what she had seen: a great fish, as long as ten men laid end to end, and with a cold, dead eye the size of a rice bowl in its glittering face. It had snapped up the small girl the way a carp would snap up a mosquito, without even pausing to chew.

Raina tore at her hair in horror. For one harrowing moment she balanced on the edge of diving into the dark currents to search for Pashmina, but the memory of that cavernous maw held her back. The thought of meeting the creature in the darkness and cold of its home sent a shiver through her, and shame at her cowardice brought burning tears to her eyes. Dropping to her knees in the muddy grass, she wept.

It must have been hours later when Father found her. It had begun to rain, large drops that bent the leaves and collected in rivulets that ran together and rushed down to the river’s edge.

Raina was curled in a ball, her robes sodden and heavy with mud, her eyes fixed on the roiling waters speckled with the impact of raindrops. The blood had drained from her face, leaving it so pale that at first Father thought he was looking at a corpse. When he found her still alive, he lifted her in his arms. Even through her grief, Raina was comforted by the rare embrace.

“Pashmina?” he asked her.

Her tears erupted anew as, through sobs, she told him of the monster who had taken her sister. She half-expected him to disbelieve her. She was having a hard time believing the evidence of her own eyes; she wasn’t sure what she would make of the story coming from someone else.

But the grim set of his jaw and the thunderous pain in his expression told her that her account was not as much a shock to him as she had expected.

“What was it, Father?” she asked him, raising her voice to be heard over the pounding of the rain as he carried her home.

“I don’t know, but there have been whisperings, tales told in the village by traders passing through from the south. Some say they are evil spirits, sent from the dark lands to take revenge upon men for settling in this sacred country, and for the crimes committed against the tribes who lived here long ago.”

Raina ached with loss and felt the stirring of something else, too, something less painful but more powerful: anger. Why should the old ones have taken their revenge on her innocent sister? Pashmina had never hurt anyone, had not even known anything of the world but her family and her forest and her playthings.

“Others say they are creatures of the wilding sea, who got lost on their way to their summer spawning grounds and slipped into the river where it meets the delta, many miles to the south.”

They neared the hut now, and Father set Raina down awkwardly on her feet, winding his own warm wrap around her shoulders with more tenderness than he had ever shown her in her life. She felt guilty at the pleasure it gave her, as if she was somehow benefitting at the expense of her sister’s life.

“Stay here, Raina,” Father said, “while I go in and talk to Mother.”

Gratitude and relief welled up within her. She had been dreading the moment of telling Mother since the moment she realized Pash was gone forever. She didn’t know if she would have had the strength to stand before her and confess face to face that she had failed in her responsibility to protect her beloved youngest sister. The relief was short-lived, however. Moments after Father pushed aside the straw door and stepped into the light beyond, a terrible wail of anguish rent the air, seeming to reverberate off of the trees in every direction. Over and over the wail repeated, raw and strangled, the sound of a soul on fire, burning and burning without end.

***

No one blamed Raina for Pashmina’s disappearance, at least not to her face. But on her weekly trips to the market, she could feel eyes on her, following her as she did her errands. Sometimes she could hear the remarks muttered behind hands and tapestries as she passed by.

“She says it was a fish the size of a house. Who can believe this?”

“More likely the girl just wandered off and the sister is afraid of getting in trouble.”

“If you ask me, she was probably off making eyes at the Elder’s son and not looking after the little one at all. I saw them at twilight two weeks ago, slipping away together into the forest.”

It was this last speculation that burned, because it hit so close to the truth. Hadn’t she been in a rush to see Arjun when she took Pashmina to the river? Hadn’t she been been daydreaming instead of paying attention to the small child in her care? If only she had watched her more closely instead of worrying about the stupid water jars and her own afternoon plans. She had known that Pash tended to wander, to forget what she had been told. But Raina had been so wrapped up her own selfish desires that she hadn’t given her responsibilities a second thought until it was too late.

Too late! Too late! The words rang in her mind as she did her chores, as she cooked dinner, as she avoided meeting the red-rimmed eyes of her mother across the table. It was too late to make amends.

Over the weeks that followed Pash’s death, Raina withdrew from family, from friends, even from Arjun, who had tried several times unsuccessfully to draw her attention as she went from shop to shop in the village.

Then, on the first day of the Festival of Two Moons, the healer’s son Efud went missing.

The men formed a search party and combed the forest for the teenager. Emissaries were sent to nearby villages to ask if the boy had been seen, but there was no sign of him. Finally, a week later, a pair of boys fishing near the bend of the river, where its waters turned to flow east past the peaks of Ferranak, found one of Efud’s red leather sandals and the small book in which he always scrawled poetry. Both items were mud-splattered and pressed into the soft soil of the bank as if by a great weight.

That night, the Elder came to their hut to ask Raina to tell the story again of the beast who had taken Pashmina. When she dared to lift her eyes to his, she saw belief there, and slowly the terrible cord of anger and guilt that had bound her heart since that day began to unknot.

A great meeting was called in the square the next day, and at the Elder’s request, Raina repeated the details of her account for the villagers. This time no one whispered. The elder’s involvement must have lent her credibility, for she saw in their faces none of the suspicion or reproach that had been there before. Only a dawning fear. She took no satisfaction in it.

In the front row, Arjun’s face as he watched her was a mask of sadness and confusion.

The meeting went long, as people threw out suggestions for dealing with the menace.

“We can hunt the monster with spears! We’ll bait it and draw it to shallow water, where we can stab it dead!”

“We’ll sew a dozen nets together and toss them from the shore to catch the creature and club it. With luck, we’ll eat like kings this winter!”

At each suggestion, Raina felt her heart sink within her, for she knew that no spear could pierce that jeweled hide, that no net could hold up under the weight and strength of that massive body.

At last, it was agreed that a group of four strong men would take a boat to the middle of the river. Armed with swords, strapped with daggers, and carrying long spears, they would wait for it to appear and then attack it all together, bleeding it from a dozen cuts until it foundered and died.

Raina knew a moment of panic when Father’s name went into the bowl to be considered for the task. She held her breath as, one by one, the four names were drawn, and let it out each time another man was called instead. The last name drawn, however, was Arjun’s, and Raina’s knees nearly buckled beneath her.

He’s just a boy! she wanted to shout as Arjun stepped forward to stand with the others. Instead, she stared at him in dismay, realizing with some surprise that he was taller than two of the men and, though young, just as heavily muscled as any of them. There was no objection she could make.

His eyes found hers among the crowd, resolute and sad, and a wordless conversation passed between them. He was doing this for her, and for her sister. She wished now that she hadn’t pushed him away, that she had turned to him with her grief and said something, anything, that would have kept him out of that boat.

Once committed to action, the men wasted no time. Filling a flat fishing vessel with supplies, they pushed out to the center of the current and dropped the large, iron anchor over the side. Old Ranuk, the baker, stood in the stern of the boat, his spear at the ready, and Arjun did the same at the front. The other two men clasped the oars, their daggers sheathed at their sides. Though the waters pushed at it, the anchor held, and the boat stayed in place, swaying only slightly from side to side in response to the passing eddies.

At first all the villagers stood on the shore and watched. Some of them laid blankets and mats on the ground, where they sat eating and laughing as if they were spectators at a game of banto ball. An hour passed. Then three. Nothing happened. As the sun fell below the trees and a chill crept over the forest, people grew bored and began to slip away. In ones and twos they walked back to their warm huts and their ready dinners, until no one was left except Raina’s family and the healer, who stood cold and aloof in the shadows beneath the trees, staring across the water as if at a great void.

In the boat, the oarsmen and the spearmen had switched places, and the men seemed to be taking it in shifts to rest while the other three stayed on watch.

“Come, Raina,” Mother said, slipping an arm around her shoulders. “This may be an endeavor of many days and nights. You need food, and sleep.”

They were the first soft words Mother had spoken to her since the day Pashmina died, and part of her wanted nothing more than to give in to their warm urging. But she could not. The river called on her to stay, to hold vigil, to witness.

“I’d like to watch a little longer,” she implored.

With a nod from Father, Mother gave in.

“Don’t be too long, asha,” she said, using an endearment Raina hadn’t heard since she was a small child. She tucked Raina’s shawl in more tightly and kissed her on the cheek, then turned to follow Father back down the path toward home.

Minute by minute the dark grew heavier and a ghostly mist rose over the ground like a restless spirit rising from the grave. Raina shivered. The healer remained motionless, a tree rooted to the spot. Time passed and lost all meaning in the passing, as if she and the healer and Arjun and the silent men in the boat were all suspended in an eternal moment, unable to go back, unable to move forward–frozen here beneath the unchanging evening sky, the river flowing on and on forever beneath them.

The moon rose slowly above the trees, breaking the spell and casting a blue and silver light along the silhouettes of those in the skiff. It sparkled off the moving water in glittering flashes, and Raina couldn’t help but think how beautiful it was, and how sad it was that she had never before thought to visit the river at night. It seemed wrong to find beauty in this night, in this terrible errand of justice and revenge.

It happened so fast, she didn’t even scream until afterward. One moment her eyes were on the boat, and the next the horrible pale shape from her nightmares had reared out of the water, capsizing the vessel and throwing all of its passengers into the river. If anything, the monster was even bigger than she remembered, and the moonlight that had seemed so lovely just a moment ago now reflected cold and alien upon its silvery flesh.

In a flash, the thing disappeared into the roiling blackness, leaving the smashed craft to be swept downstream. The men were foundering, weighed down by their heavy weapons. They pulled toward the bank, but slowly, too slowly, reluctant to give up their iron blades.

“Arjun!” shrieked Raina, “Arjun! Drop your sword and swim!”

Just behind him, Old Ranuk gave Arjun a shove in the direction of the shore. “Faster, boy,” he croaked through a mouthful of water. “I’m too old to carry you on my ba–” His head disappeared beneath the surface suddenly, as if he’d been yanked downward with great force.

That is exactly what happened, Raina realized, and her shouts became screams. “Arjun! ARJUN! HURRY!”

She watched in growing horror as the other two men were picked off one by one, their bobbing heads winking out of sight as they were pulled down into the icy depths.

The healer was standing at the edge of the bank now, leaning down, his hand extended to pull Arjun to safety. Arjun kicked wildly, throwing off his weapons and using both arms to make long strokes toward safety.

He was ten feet away. Now five feet away. Praise the old ones! He was going to make it! As he drew close enough, he reached out his hand to meet that of the healer.

Then, just as their fingertips brushed against each other, a spasm of pain flashed across Arjun’s handsome face. His hand was yanked violently away as he too was seized and dragged below the water. Just like that, he was gone.

The healer fell back and scrambled away from the water like a crab. A strange sound came from his lips, something between keening and gibbering. He sounded crazy. He wrapped long, bony arms around his knees and rocked back and forth in the mud.

Raina was in shock. How could this be happening? Arjun, her friend, the boy that she loved, was gone forever. Just like her baby sister. Just like the healer’s son. Just like Old Ranuk.

How many had been killed that they didn’t even know about? How many more would die tomorrow?

Four armed men had been taken in the night without even a fight, right in front of her eyes. How could this be? Surely this creature, this monster, was no mere animal. It struck without warning and brought unchallenged death to all who crossed it. It’s cold savagery reminded her uncomfortably of the stories Mother had told her as a child, stories of the old gods. Those giants and leviathans who had crawled the scabby surface of the newly forged world had dealt in death and madness, demanding worship from the ant-like masses beneath their sway. In return they had offered temporary relief from the terrors they themselves wrought. Could this demon be one of those, woken from its slumber in the deep places and returned to bring down wrath on a people grown indulgent and forgetful of the old ways? Her parents would scoff at that. But she who had borne witness could not.

Suddenly Raina knew what she must do.

***

The night was colder now.

At any moment Mother or Father could come looking for her. She would have to hurry. The tiny fishing dinghy that she and Arjun used to play in when they were children was still leaning up against the clump of ash trees behind the hut. The sight of it filled Raina with sadness. Pashmina would never know the fun of piloting the craft among the reeds and shoals as she had, would never grow old enough to run with her friends through the sun dappled forest on a summer day or enjoy the excitement of falling in love with a boy. Raina’s heart ached for all that was lost.

Silently she stole across the grass, careful to avoid the lantern light streaming from the windows of the hut. She must not let them find her, must not let them stop her.

She lifted the boat from its place–it was so much lighter now than when they were children–and carried it on her shoulder as she followed the same well-worn path that had led Pashmina to her fate those long weeks ago.

When finally she reached the water, she stood for a moment in the moonlight, wondering if her resolve would flicker. It did not. This was her path, she knew, and despite the fear that tried to strangle her, she would walk it.

The boat still floated. Of course it did. Raina gave it a small push, and in the same smooth motion, leapt aboard, as nimble as a gazelle. Using the boat’s one paddle, she moved out into the current and pulled for the other side, looking for the place in the middle where the eddies would hold the craft relatively still. When she found it, she threw the oar overboard. After all, she would not need it again.

Acting purely on instinct now, she stood up, balancing carefully, and began removing her garments one by one. First, the shawl that Mother had made her for her sixteenth birthday, silky and cream colored, embroidered with small flowers the vivid blue of a cloudless sky. She threw it into the roiling water, followed by the wooden pendant in the shape of a leaf that Father had carved for her when she was born. It was delicate and detailed, and she had cherished it as evidence of the loving heart behind his gruff exterior. The water sucked them down like a greedy animal. Her dress, the first she had ever sewn by herself, she drew over her head, and her bare flesh raised in goosebumps against the cold. Last, she kicked off her shoes — good, strong canvas shoes that had carried her feet down many roads, all of which had somehow led her here, to this place. To this moment.

At last, she stood naked in the moonlight, exposed to the eyes of whatever watched from the skies above or the water below. She didn’t know how she knew it, but this was right. This was hers to do, hers to give. Only hers. From this night on, no one else would die.

Spreading her arms wide, as if to embrace the sky for the last time, she let herself fall backwards into the black water, gasping when the cold of it hit her bare skin. Her immediate instinct was to fight, to swim, to grasp at the surface with panicked strokes. Instead, she forced herself to relax, to let go, to allow the inky embrace of the river to close over her head. Down she drifted, down and down, until her lungs were nearly bursting with her last breath, and then she let that go, too.

Come, she thought, mentally projecting the words out into the river, come and take your virgin sacrifice. I am willing.

There was a moment of panic as she breathed in water, feeling the burn in her oxygen-starved chest, but it passed quickly, and a peaceful darkness began to blur the edges of her consciousness.

The cold caress of diamond-hard scales brushed against her side, and she knew, vaguely, that it was almost over. She couldn’t see anything, but she could feel the hulking presence of the one she had called as a great volume of water gave way in a rush before it. There was one last terrible impact. And then she felt no more.

Wow! That was intense! Beautifully written and so, so sad.

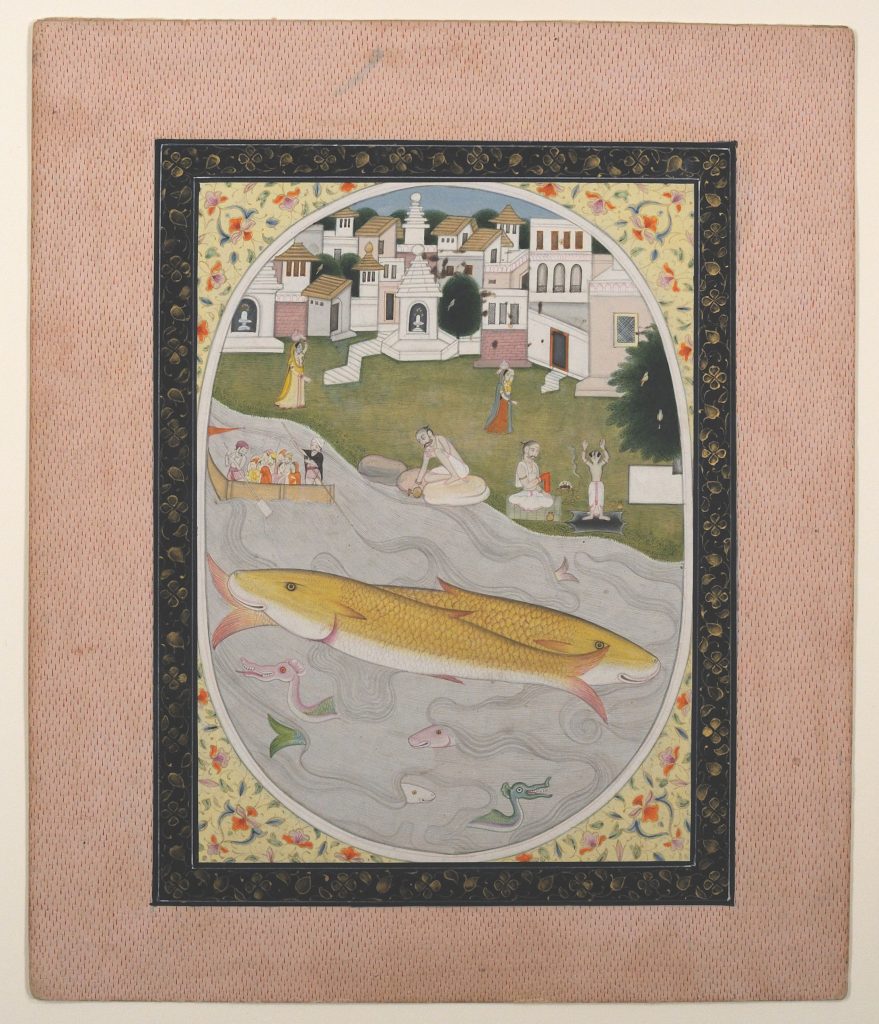

Thank you! Strangely, I didn’t know how the story was going to end when I started it (I just jumped in using the painting I posted as a prompt), so I discovered the true nature of the monster at about the same time as the protagonist!